How The Finger Lakes Was Named: Part 2

The following post about how the Finger Lakes was named is the second in a two part series. You can find Part 1 of this series here.

by Michael Brewster

Part Two…

Earliest Colonizers

If we can’t rely on “An Old Indian Legend” to tell us how the Finger Lakes got named, then we have to look at more recent history, starting with colonial times.

I have been researching Haudenosaunee/Colonial New York history for nearly a decade and have been writing about my research for the past couple years. I have combed through the oldest written records of French contact with the Five Nations that took place in the mid-1600s, and at that time, the main lakes being written about were the Great Lakes, which makes sense. French explorers were looking for economic resources like beaver pelts as well as waterways that might lead to the Pacific Ocean.

In the 1650s, several French Jesuit missionaries were set up in what is now Central New York, including one on the north shore of Onondaga Lake and one on the eastern shore of Cayuga Lake. Nowhere in their records do the French write of the Finger Lakes or even consider these small inland lakes as a group.

However, looking at some old maps, the larger lakes like Canandaigua, Seneca and Cayuga do stand out, mainly because they are connected by their outlets. But these maps generally include Onondaga Lake and Oneida Lake because of their connections to the other lakes via the Oswego and Seneca Rivers as well as their strategic importance as being near Five Nations villages.

What About Oneida Lake?

Actually, historically, Oneida Lake, a one-mile portage west of the Mohawk River, was the most important lake south of Ontario. South of Oneida, the smaller Cazenovia Lake drains into Oneida near the present-day Bridgeport, New York. Oneida drains at its western end into the Oswego River, which connects to the Seneca River north of Syracuse.

The Seneca is connected via outlets to Otisco Lake (Ninemile Creek flows into Onondaga Lake, which outlets into the Seneca River), Skaneateles Lake, Owasco Lake, Cayuga Lake and Seneca Lake. Canandaigua Lake outlets into Canandaigua Creek, which feeds the Clyde River before joining the Seneca River.

So, from Oneida Lake to Canandaigua Lake, there is a nine lake interconnected waterway. If the colonists, French, Dutch or English were to name a set of lakes as “Finger Lakes,” this whole system would be a prime candidate.

However, Oneida Lake is not situated on a north-south river valley, and is relatively shallow (55 feet), though it has nearly 25 times the surface area of Otisco Lake. Onondaga Lake is very similar to Oneida, a relatively shorter and broader shape than the long-fingers of Skaneateles, Cayuga and Seneca.

After the Revolutionary War

So, the name “Finger Lakes” must have been applied after the Revolutionary War, and my first inclination was to research the time when the New York frontier opened up to the Erie Canal, roughly 1800-1825. Prior to that war, western settlement was halted by the Treaty of Stanwix (1768), which recognized the lands west of Fort Stanwix (present-day Rome, NY) as belonging to the Six Nations of the Iroquois, who call themselves the Haudenosaunee (People of the Longhouse). After the Revolutionary War, this line was crossed and by the late 1790s, Central New York, west to Seneca Lake, was being settled. Still, the area from Seneca Lake westward was unsettled, until the 1797 Treaty of Canandaigua opened the area to white settlers. One promising candidate for study was Volume II of the Collections of the New York Historical Society published in 1814. This book compiles various lectures and essays about New York State, including a “Catalogue of the Books, Tracts, Newspapers, Maps, Charts, Views, Portraits, and Manuscripts in the Library of the New York Historical Society.” Though one part names 20 lakes across Upstate New York, including all eleven of what we call the Finger Lakes (using “Crooked” in place of Keuka), the book does not include the all-important phrase “Finger Lakes.”

Henry Gilpin’s Early Upstate Voyage

In Part One of this article, we met William Darby when he described the beauty of the Village of Canandaigua in his book A tour from the City of New-York, to Detroit, in the Michigan Territory… (1819). Because his geographical discussions are extensive, the book warrants a further examination. On page 153 he describes a series of hills with their ridges parallel to each other (we call these drumlins) and parallel to “chain of lakes which form the Seneca river.” He uses “chain of lakes” again on page 215, and just two pages later, he writes half a page in particular detail about these lakes (see screenshot), which is a perfect place to name the group, but he doesn’t. Instead, he likens the Valley Heads terminal moraines to a spine, from which the ridges between the lakes “diverge like the ribs of an animal.” Two pages later he says “The Skeneateles (sic) is in form similar to Seneca and Cayuga” without making any comparison to fingers. As he proceeds eastward, he describes the lake country as possessing a “regular and almost artificial aspect.” In one of his appendices, he describes the ancient boundaries of Lake Ontario, speculating, correctly as it turns out, that some of the lakes were bays back in the immediate postglacial period.

This type of travelogue was pretty popular back then, and in 1825, Henry D. Gilpin published A northern tour: being a guide to Saratoga, Lake George, Niagara, Canada, Boston, &c., &c., in which he describes the interconnectedness of our lakes. He describes how the waters of Seneca and Cayuga Lakes run together, and are joined with “waters of the Canandaigua, Owasco, Skeneateless (sic), Otisco, Onondaga, and other smaller lakes.” grouping them together, he calls them “all the lakes of ‘the lake region’” and not, disappointingly, any proper name. Notwithstanding his lack of a catchy name for our region, I think the combination of geology and hydrology here, that the relatively small Oswego River drains several thousand square miles of Upstate is quite an impressive fact. Of course, in comparison to the Niagara River and its drainage of four Great Lakes, this is nothing, but at least all of the Oswego’s flow originates completely within the boundaries of New York State.

Pre-Civil War Gazetteers & Other Near-misses

Before I wrap up this examination of Pre-Civil War sources, here’s a quick list of other books that would definitely talk about the Finger Lakes if there were such a name, but don’t…

A “gazetteer” is a book that is essentially a geographical dictionary. Horatio G. Spafford spent three years and $7,000 compiling the Gazetteer of the state of New York, which was published in 1813. He tried to recoup the costs of this book and make money compiling gazetteers for other states, and to this end sent a copy to President Madison and also former President Thomas Jefferson. In a letter to Jefferson, he wrote:

“My intention is to pursue the plan of writing, & form Gazetteers of the

several States; then separate the parts, & form a Geography, & Gazetteer,

of the United States, in separate volumes.”

To this end, a comprehensive book would be invaluable. However, it does not have a listing for “Finger Lakes.” The closest he comes to mentioning the area is when he writes: “The inland trade through the Mohawk and the small lakes.” The “small lakes” are the Finger Lakes, compared to the “Great Lakes.” While he missed his chance to name the Finger Lakes, the town of Spafford, on the shore of Skaneateles Lake in southern Onondaga County, is named for Horatio. Historian William Beauchamp tells us:

“The town received its name in 1811, from Mr. Spafford who bought

land there, intending to settle, and offered a library to the town if it

received his name.”

In 1827, our friend William Darby publishes Darby’s Universal gazetteer, or, A new geographical dictionary and as much as we know his love for Canandaigua (from Part One), he does not mention the Finger Lakes as a group. The 1836 Gazetteer of the state of New York by Thomas F. Gordon also omits any reference to the Finger Lakes. John H. French published Gazetteer of the State of New York: embracing a comprehensive view of the geography, geology, and general history of the State in 1860, and this book also omits any reference to “Finger Lakes.”

Considering that all these gazetteers were leading to dead ends, I decided to look at the New York State Museum publications, hoping that somewhere in the mid-1800s, some scientist or natural historian would have coined the Finger Lakes name. A comprehensive 30-volume Natural History of New York was published in 1842, including several volumes on geology, but again, no “Finger Lakes.”

The last of our “near-miss” sources came from a hunch I had about how we describe the Finger Lakes. In many sources, you might see “Finger Lakes Region” and in some older ones the wording is “Finger Lakes District” instead. So, searching for this latter version gave me some results, mostly in the 1920s and 1930s. But searching a variation, I found a transcription of an article by Rev. R. B. Welch called “The Lake District in Central New York” from a magazine called Ladies Repository dated October 1864. While this article does not use “Finger Lakes,” it is definitely an article about the whole area, so if our term were in use in 1864, it would by all rights be in this story, but it is not. Welch describes the five lakes like this:

“After spending a few days at Trenton Falls whose charm grows upon us

with each renewed visit, we pushed forward to Cayuga, the largest of the

group of five sister lakes, reserving Skaneateles and Owasco for our return.”

Trenton Falls is on the upper West Canada River north of Utica, and happens to have been the site of some world-class fossil finds a few decades after this article was published.

These Sources Definitely Use Finger Lakes

We ended Part One with a book from 1920 by Seneca County Historian Fred Teller. So we have a window between 1865 and 1920— 55 years during which the term Finger Lakes was invented and blossomed into widely-accepted usage. With that as a clue, I thought there might be some popular publication, some book, that popped up and everybody read, but I didn’t find one. But since Mr. Teller had used the name Finger Lakes in the title of his 1920 book, I looked for something he had written at an earlier date to see if he used the term then.

1904

In the 1904 publication Centennial Anniversary of Seneca County, Teller contributed two articles, one on the Seneca Indians and one on an early settler to the area. He did not use the “Finger Lakes” in either article, but I was happy to find that the Hon. Diedrich Willers (former NY Secretary of State) did in his “An Historical Address.” Apparently, this publication printed speeches that were given on at the centennial celebration and in a mention of the 1779 Sullivan Campaign, Willers says: “… in the lake region of Western New York, in which are found the ‘Finger lakes’ so called.” Despite his awkward phrasing, Willers has pushed our documented use 16 years back to 1904.

1902

In a Rochester Democrat and Chronicle article (26 April 1902) on flooding in New York and the State’s forming a commission to deal with flooding in rivers, we find

1900

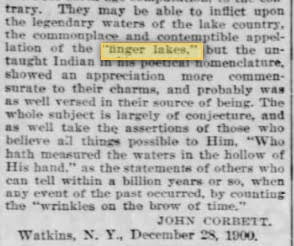

Also in the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, an letter to the editor (29 December 1900) about the topography and geology of New York. John Corbett of Watkins, founder and publisher of the weekly Schuyler County Chronicle, who dismisses “10,000,000” years ago as the time of creation for the rock formations of Watkins Glen, and instead places them in glacial time along with the Genesee valley and Niagara Falls. Interestingly, though he uses “finger lakes” as a phrase, he does so disparagingly, finding it “commonplace and contemptible.” Interestingly, he seems to refer obliquely to the Indian name of the area, and makes a connection between the Biblical “Who hath measured the waters in the hollow of his hand” (Isaiah 40:12), which would push the idea of the “Old Indian Legend” back from 1920 to 1900, but I don’t quite give him credit here as he doesn’t explicitly refer to it. One last tidbit about John Corbett: he descended from pioneers who settled the area, Asaph Corbett having bought a farm in Catharine in 1804.

1899

A lecture on local geography by Professor Herman L. Fairchild was reviewed in the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle on March 31, 1899. This usage was not capitalized and placed in quotes just like the 1900 Corbett version.

1891

Topping our list of newspaper geology articles, the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle of October 13, 1891 published a pretty technical article by Charles R. Dryer of Fort Wayne, Indiana. In this article, Dryer uses “finger lakes” twice, both times not capitalized and in quotations.

So, we have narrowed our window of invention to the 1865-1890 period, and if the above newspaper articles are any indication, it seems that the words “finger lakes” not capitalized, and in quotations as if still tentative as a name, are used in newspapers but have come from the world of geology.

Onward we go!

Scientific Articles

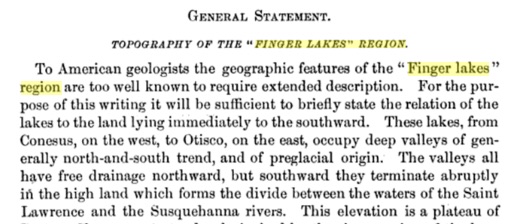

Remember Professor Herman L. Fairchild, who lectured about the geology of the Rochester area in 1899? He was Professor of Geology and Natural History at the University of Rochester from 1888 until his retirement in 1920. In 1895, he read a paper, called “Glacial Lakes of Western New York” before the Geological Society of America, which was published in their Bulletin dated April 12, 1895.

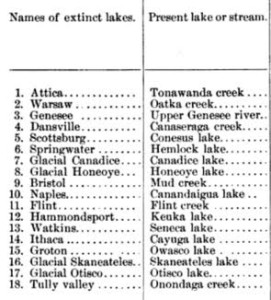

In this paper, Fairchild covers, quite extensively (20 pages), the topography and geology of the what we now call the Finger Lakes region, including an additional seven river valleys that once had lakes (dating back to glacial time— 12,000+ years ago), but now only have rivers and creeks.

Though he fails to use “Finger Lakes” in his title, Professor Fairchild’s introduction is titled “Topography of the Finger Lakes Region” and in the body of his article, he capitalizes “Finger” as a proper noun. Throughout his article, they only capitalize the name, not the “lake” so you read of “Seneca lake” or “Keuka lake.” Conventions have changed since then, obviously.

As impressive as Professor Fairchild’s article is, the date is 1895 and we already have an 1891 reference from Dryer, so this is not our origin. But if you search scientific material from the 1890s, you will find many “Finger lakes” references.

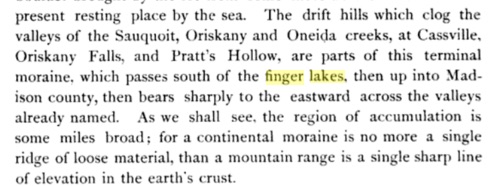

With a date of March 4, 1891, a lecture by Professor Albert Bingham of Colgate University to the Oneida Historical Society beats Dryer by seven months.

In this lecture on the glacial history of New York, Bingham talks about a terminal moraine “which passes south of the finger lakes, then up into Madison County…” A moraine is essentially a dam of rocks and soil left by the bulldozing action of a glacier and a terminal moraine is this line of rocks and soil built into a huge ridge that can block a whole valley, creating a lake.

The moraine that holds in the Finger Lakes on the south end is called the “Valley Heads Moraine” and basically separates water that flows north to the St. Lawrence River from water that flows south to the Susquehanna River. In this respect, it is a Continental Divide.

The Oldest Reference Found So Far

In 1893, Ralph S. Tarr presented a paper to the Geological Society of America about the geology of Cayuga Lake specifically. He added a survey of all the literature published on the Finger Lakes region to that point, a list of just over 20 articles and books dating back to the 1842 volume on New York we already examined. I had found a reference to the Finger Lakes in a report dated 1883, and I was excited to have this list with some promising articles from 1877 and 1881 to check out. But alas, the 1883 article I had, by Thomas Chamberlin, which Tarr cited on his list, turns out to be the earliest reference to “Finger Lakes” that I can find.

Chamberlin was a respected and influential American geologist and science educator, who supported the concepts of multiple glaciation and planetesimal origin of the Earth. He held several different teaching, research, and administrative positions, often concurrently, during a long and fruitful career. Among the more important positions were Professor of Geology at Beloit College, Wisconsin (1873-82), Wisconsin State Geologist (1876-82), chief of glacial division USGS (1881-1904), President of the University of Wisconsin (1887-92), chairman of the Department of Geology, University of Chicago (1892-1919), and President of the Geological Society of America (1894). While at the University of Chicago, he founded the prestigious Journal of Geology.

The article in question here is the influential Preliminary paper on the terminal moraine of the second glacial epoch, an 1882 monograph published by the United States Geological Survey, which is collected in their Annual Report Vol 3 of 1883. His reference is innocuous enough: “…covering the territory of the divergent finger lakes…” and he uses no capitals, so to him it is clear that these are just adjectives, not a group name. But is this really the first use of “Finger Lakes”?

I feel like this is the first use of the term based on an analysis of two textual features:

- Chamberlin does not use quotation marks, he does not say “so-called” and he is not titling the whole region. Instead this is simply a description that fits.

- The lack of capital letters indicates regular language, simple adjective + noun, and not a title or name. In Ralph Tarr’s article, he credits other scientists with their ideas, and if Chamberlin had borrowed this term, his science would have been strengthened by giving the earlier reference.

There we have it!

Until someone can find a pre-1882 reference, I am happy with Thomas Chamberlin, a professor from Wisconsin, being the person who named our lakes. Additionally, Professor Fairchild’s 1895 table of extinct lakes lists 11 Finger Lakes, giving definitive scientific proof of the number and identity of these lakes. Sorry, Cazenovia, Onondaga, Oneida, Lamoka, Silver and any other lake.

Resources and Additional Reading

Spafford to Jefferson Thomas

Beauchamp on Spafford

1842 Natural History of New York

Welch article

H.L. Fairchild

Born and raised in Central NY, Michael Brewster has traveled the US extensively, but is most at home in the Finger Lakes. The beauty and history of Upstate NY continue to marvel and fascinate him. He enjoys local food, beer and live music. Find him on Twitter @brewcuse

June 4, 2016 @ 12:20 am

Brewcuse,

We have reached the end of your two-part series.

We suppose that we should start this critique at the beginning: Why did you choose to emphasize the history of naming the lakes by gathering resources from strictly Anglo-originating sources? Should English readers assume that there were no names applied to geological formations before the advent of white skin? Why did you completely ignore the oral history of the Haudenosaunee? It is an insincere apologia to court the countryside. The water has been here before us.

With all politeness, your perspective is askew. There is no point in naming that which is, already. Furthermore, by simply calling this area the “Finger Lakes,” one is adhering to folklore & religiosity. Attempting, as you do, to apply the scientific approach of European “Enlightenment” does nothing more than short-circuit the importance of breathing in what you have called the Finger Lakes. There is no interaction, it seems, beyond exploitation and extermination: By the same names that named the Finger Lakes. The real concern should be not from which the Finger Lakes was named, but for how to revise a future where the Finger Lakes is secure.

Since you understand the land and its history, we believe that you have a strong connection to its preservation. We look forward to your piece about the perils of the hydrofracking industry, with special attention to how it will change the name of the Finger Lakes.

Cheers,

Hayduke and Bonnie

June 4, 2016 @ 11:56 am

Hello Monkeywrenchers!

As a guest poster on this blog, I had one goal for the article- to explore how the name “Finger Lakes” came to be applied in English to a geological feature that pre-existed the English as a colonizing force and as a language in and of itself. In doing so, I was limited in several ways: to write something for an audience of people who might want to learn some history and also to write something short.

I started with the question “Why is Oneida Lake not considered one of the Finger Lakes.” In doing so, I also had to consider Onondaga’s status as not a lake like the others, but I could not go deeply into the particular and specific sacred centrality of the lake to the Onondaga Nation and the Haudenosaunee as a whole for two reasons. One, I am non-Native and I take my status very seriously. I don’t feel I have the authority to pass along oral traditions that are not mine, but I did, in the first part, quote from David Cusick, which is a widely-available retelling. As a non-Native scholar, I respect that there are stories and traditions that are not mine, but as a person who has Native friends and family, I recognize that what passes in the Anglo tradition as “Indian lore” is often fictional and repackaged truths that separate ideas from reality. I felt the need to illuminate Anglo lore passing as Indian truth. This forum is too limited to address all, so I purposefully chose to limit my inquiry into, admittedly, the format of Enlightenment-based epistemologies and not as Professor Daniel Heath Justice, Cherokee, calls them, “other ways of knowing.”

With all politeness on my part, I disagree that these two articles should have had any purpose other than that which they are, a relatively simple and straightforward discussion of a region of colonized New York. You might be interested, or you might not, in my further work on the Finger Lakes region (using the English name because I am not claiming to be part of another’s tradition) looking at how the colonizers “invented” the area, though, as you point out, it did already exist. If we can understand truly the misconceptions and mistakes of our predecessors, I believe that we can reach a future where the Lakes are again respected and protected.

Finally, personally, I have supported the We Are Seneca Lake efforts with time and money, and I have written on some environmental issues surrounding the Crestwood LPG plan. I know that this article does not address any of that, but as I stated above, as a guest in another’s home, I respected the host. Because I am writing an environmental history of the Finger Lakes that includes the colonization of the Indigenous peoples (mainly Haudenosaunee), I would invite anyone who cares to talk to me about other perspectives so that I can learn. I am sorry that the scope of this article did not reach as far as you had liked, but I am not finished with my work. I have read James Thomas Stevens, Eric Gansworth, Maurice Kenny, and Beth Brant and they urge me to keep going on my journey.

Thank you for taking the time to read my words and open a dialogue.

Michael

March 3, 2018 @ 10:32 am

What fun! I love good documented research.

How The Finger Lakes Was Named: Part 1 |

March 11, 2019 @ 9:40 am

[…] CLICK HERE TO READ PART TWO of How the Finger Lakes Really Got Their Name […]