Inventing the Adirondacks: Camp Pine Knot

by Michael Brewster.

In 1877 when William West Durant set about building a permanent camp on a small peninsula on the south side of Long Point in Raquette Lake, he might have thought he was creating something of a legacy, as wealthy men of his generation might have done in any aspect of their lives. However, he probably did not set out at the time to single-handedly invent what we have come to know as the Great Camp Style.

I do not mean to credit W. W. Durant with the invention of all things Adirondack, but looking back almost a century-and-a-half into New York’s past, we can pinpoint the rustic architecture and furnishings style that persists to this day as emanating from Durant’s building of Camp Pine Knot. Durant drew his inspiration from the even-more-rustic hunting and logging camps that existed throughout the wild mountains. Miraculously, Pine Knot exists today almost unchanged from his original design and is a preeminent center for Outdoor Education and a National Landmark. Durant sold the camp to Collis Huntington to settle debts and went on to build two other Great Adirondack Camps— Uncas and Sagamore.

Describing the Adirondacks

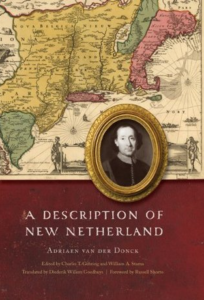

The Adirondack Mountains, one of America’s first great wild parks, were apparently named after an insult. The Mohawks, who settled just south of the mountain range in a broad fertile river valley, named the Algonquin peoples to their northeast some form of atirú:taks, a word referring to porcupines and generally translated as “bark eaters.” The mountain region was not permanently settled by either people, but used for hunting grounds dating back thousands of years. By the 17th Century, when the beaver fur trade with the colonial Europeans exploded across the area, the name had been corrupted in both Dutch and French. The name was perhaps first published (describing the Algonquins) as ‘Rondaxkes’ in A Description of New Netherland (1655) by Adriaen van der Donck. The Mohawk language, Kanien’keha, also calls the region Kohserà:ke, meaning “place of winter” or Tsi Kario’tanákere “said to be the place of animals.”

The American geologist Ebenezer Emmons named the mountains ‘Adirondacks’ in 1837 while on an expedition to explore this wilderness. His 1838 report might have been the first “guidebook” to the area, but the book that really sparked development was The Adirondack; (or, Life in the Woods) by Joel Tyler Headley. This book, revised and expanded from 1849 through many editions, became the book that first promoted the idea of the wilderness as a healthy getaway, which led to the building of hotels and roads to reach them. Simultaneously, the Adirondack Wilderness was explored and documented. Plans were developed to exploit the lumber resources and various mining concerns sought to do the same with minerals, always hoping for gold or silver. By 1868, William Henry Harrison Murray’s Camp Life in the Adirondacks expanded on the wilderness idea, claiming that the rustic lives of the mountain men were healthy and spiritually better than living in cities. Though Murray may have been writing to save the wilderness, his readers romanticized his message and began streaming into the area for summer vacations.

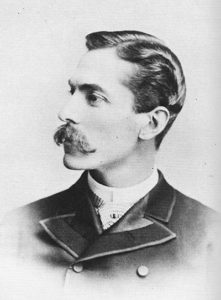

Railroad magnate Thomas Clark Durant, vice-president of the Union Pacific, built the Adirondack Railroad from Saratoga Springs northwest to North Creek. He purchased large tracts of land for a railroad and made plans to bisect the Adirondacks westward from there. His son William West Durant had been educated as an architect in Europe and, as the scion of a wealthy family, traveled extensively in his youth. By 1874, there were upwards of 200 hotels in the Adirondacks and the elder Durant summoned William back to New York to develop an Adirondack tourism industry. W. W. Durant chose Raquette Lake as his home base and began developing permanent buildings for Camp Pine Knot.

The story of how the camp passed from W. W. Durant to the Huntington family is a familiar one. Durant and his sister were the heirs to the family fortune when their father died without a will in 1885, but he did not share much of the financial details with her. Over time disagreements became disputes and coupled with business downturns, the Durant fortune dissipated to the point that William declared bankruptcy in 1900. He had befriended railroad magnate Collis P. Huntington of the Central Pacific Railroad and sold Camp Pine Knot to him in 1895. Huntington died at the camp in 1900, and his family stopped going there. It sat neglected and forgotten until it was rediscovered by two professors from Cortland State College and bought from the Huntington family for $1 in the late 1940s with the stipulation that it stay forever the property of the College’s Outdoor Education program.

The Camp

Camp Pine Knot grew to encompass over two dozen buildings, but three of them are truly remarkable in historic and artistic terms. The first and oldest is The Chalet, sometimes called the Swiss Chalet, which recalls something of the alpine retreats W. W. Durant would have visited, but is expressed in a much more rustic native Adirondack style. The next, a large common room “Great Hall” named Metcalf Hall sets the standard for many lodge-style camp buildings throughout the Adirondacks and as far away as Alaska. Finally, Durant’s personal living quarters are fully realized as a cosmopolitan refuge in the woods.

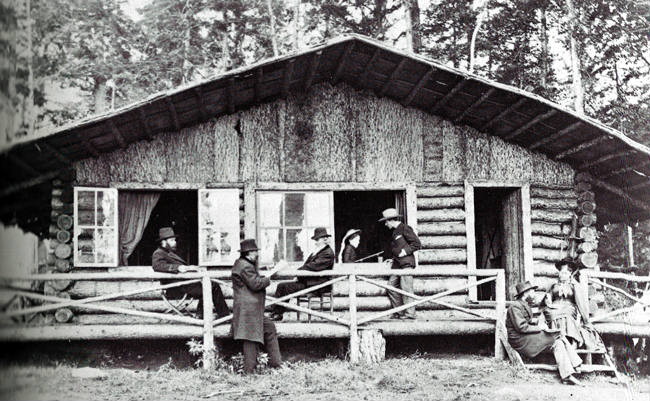

The first permanent structure at Pine Knot was known as The Chalet, a one-story building constructed of local logs and birch bark coverings. The front porch and windows overlook a grade that leads down to the dock area of the lake shore. Within a couple years of its creation, the building was more than doubled in size with the addition of a second story which actually exceeds the original floorplan, providing an overhang that covers the lower porch. This first-floor porch is open, not screened or glassed-in, and provides a wonderful place for evening relaxation.

Though the Chalet is 135 years old, minimal modern renovations have been done to the structure. It has been wired for electricity, but in many places the bark coverings are original, and on the interior, nearly all the wood is original.

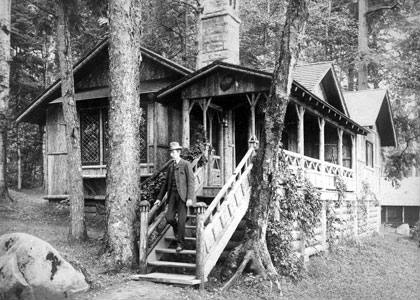

Metcalf Hall was originally built as the camp’s recreational lodge. It is a large open space with a wraparound porch and a massive stone fireplace. The huge glass windows were hand-carried from the railroad to be installed. The exterior decorations show the lengths Durant went to have his men find and collect perfectly-formed naturally bent wood to fit his vision.

Durant’s cabin has been redecorated to reflect his cosmopolitan tastes. The interior is cozy and his desk looks out over the lake.

Because the property is used year-round by SUNY Cortland for educational purposes, it may be difficult to visit. Though I’ve had some affiliation with SUNY Cortland since 2008, it wasn’t until this summer that I was able to stay at the camp for a week. On my last day there, a private tour group arranged through Raquette Lake Navigation spent an hour or two at the camp, though such tours are quite limited and book quickly.

Resources and Additional Reading

“Camp Pine Knot” on greatcamps.com

“Camp Huntington Tour” on SUNY Cortland website

Raquette Lake Navigation Company website

“William West Durant and His Adirondack Camps” on Gulliver’s Nest

Born and raised in Central NY, Michael Brewster has traveled the US extensively, but is most at home in the Finger Lakes. The beauty and history of Upstate NY continue to marvel and fascinate him. He enjoys local food, beer and live music. Find him on Twitter @brewcuse

July 5, 2021 @ 4:31 pm

Can the public visit Camp pine knot? If so, who do I make contact to see it?

July 5, 2021 @ 4:43 pm

Hey Lynne!

A tour company called Raquette Lake Navigation has various tours, and one of their tours called “Great Camps Grand Tour” includes a tour of Camp Pine Knot. You can contact them directly about getting into a tour.