Molly Brant and Her Lasting Impact on New York

by Michael Brewster

Tekonwatonti and Molly Brant

Much of the history of New York and its colonial beginnings center around the men of the time. However, for the indigenous Haudenosaunee of Upstate New York, women are just as important to their society and culture, if not moreso. This is the story of one Haudenosaunee woman, the Mohawk Tekonwatonti, known in English as Molly Brant.

Credit: History Museum of Canada

Molly Brant was the sister of one of the most important men in Colonial New York and the wife of the another. Her brother, Joseph Brant, Thayendanegea, led the Mohawk against the Patriots in the Revolutionary War, and her husband William Johnson was the man in charge of British relations with Natives in the Northern American Colonies until his death in 1774. Much has been written about Brant and Johnson, while Molly has been ignored and virtually erased from her proper place in history. This article will attempt to do her some justice. My main purpose is to introduce her to a wider audience and share more resources about her.

Modern Brant

In 1981, Beth Brant (1941-2015), a Mohawk from Canada, traveled to Central New York and the Mohawk Valley on a sort of spiritual journey to visit the lands Molly Brant lived in. Returning from this trip, she encounters a bald eagle in Western New York on a Seneca reservation. She recalls:

I saw Eagle. He swooped in front of our car as Denise and I were driving through Iroquois land. He wanted us to stop… I got out of the car and faced him as he sat on a branch of White Pine… I had received a gift. When I got home I began to write.” (“To Be” pg. 75)

For Beth Brant, this manifestation of the Haudenosaunee symbol was a sign that she was on the right track in trying to reconnect with her distant relative Molly Brant (Beth’s father’s family is descended from Joseph). She associates her writing voice with a re-connection to “Iroquois land,” as expressed in explicitly Haudenosaunee terms,the Eagle at the top of the White Pine, and from there she grew into a powerful writer and teacher.

It may be strange for New Yorkers today to think of Haudenosaunee as writers, but the Six Nations, the Mohawk in particular, have a centuries-long tradition of writing alongside their oral traditions. I begin with this small sketch of Beth Brant discovering her own writing voice because she implicitly credits that voice to Molly Brant. She wrote of Molly: “Her story has always been neglected in favour of her brother’s, Joseph; just one more example of sexist racism at work” (“Writing Life” pg. 107)

Brant Becomes More Widely Recognized

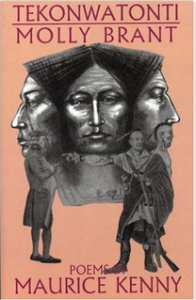

During the 1980s, there was almost nobody studying and writing about Molly Brant. One person, the Mohawk poet Maurice Kenny (1929-2016), decided to change this and he started writing a series of poems about Molly, about the Mohawk and their lands. This book, Tekonwatonti, was published in 1992 and is available today. It is very accessible, a sort of survey of Mohawk culture and history. “Beth Brant, 1981: Letter & Post Card.” In this poem, Kenny combines correspondence from Brant with his own words.

There was a dream:

Molly / Joseph

I’ve lost the language.

What does it mean, the dream?

After all these centuries’

travels across northern lands

couplings and recouplings

bloods and wars

lost.

Conceptually, the poem centers on the cycles of history, as if time swirls like water around a paddle dipped into a lake. For both Beth Brant and Maurice Kenny, the restoration of Molly’s place in Mohawk history, where she is as important as Joseph, is achieved through language. Ironically, however, Kanien’keha, the Mohawk language, in which both Molly and Joseph were literate, has been largely forgotten over the centuries. This poem captures the feeling of the two writers in 1981 of the need to recapture Kanien’keha and Molly’s history.

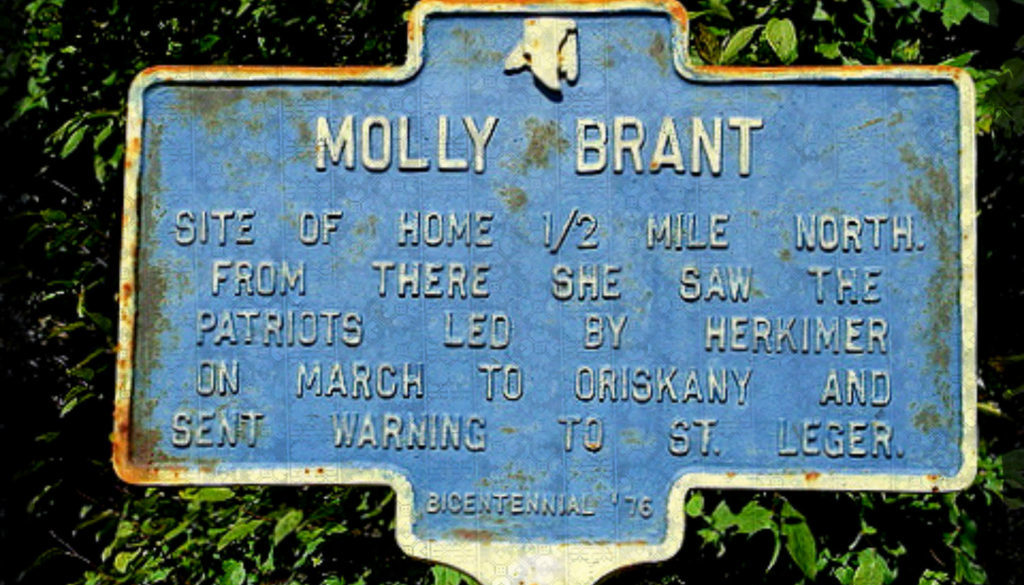

Brant’s Role in the War

During the Revolutionary War, the Mohawks militarily supported the British after an initial period of Haudenosaunee-wide neutrality. The single person most responsible for this was Tekonwatonti, Molly Brant. Tekonwatonti (~1736-1796) became the second wife of Sir William Johnson (~1715-1774), the British Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Northern Colonies from 1756 until his death, just several years after he rose to that position. As the wife of Johnson, Molly Brant held an unusually influential position in both Mohawk society, while simultaneously maintaining a visibility in Colonial American politics. Daniel Claus, a Loyalist who married Ann Johnson, elder daughter of Sir William and his first wife Catherine, who was the Deputy in charge of Indians in Canada during and after the war, wrote of Molly: “one word from her is more taken Notice of by the five Nations than a thousand from any white Man without Exception” (309). A matrilineal people, Haudenosaunee power flows from a mother’s clan to her children and while Molly’s mother is not known definitively to have been a matron, Molly’s stepfather was a sachem.

Thayendanegea (1743-1807), Joseph Brant, rose to prominence as a war chief. Tekonwatonti probably was schooled and literate in both English and Kanien’keha (Feister 304). That she was literate in her native language was not unusual, as William Beauchamp reported that by the 1760s Mohawk literacy was widespread (qtd. in Goddard 24), though the scant remaining letters written by her are in English.

Perhaps the true measure of the cultural value of literacy is contained in Molly Brant’s dedication to the schooling of her and Johnson’s eight children. Lois Feister and Bonnie Pulis write that “Johnson established a school in nearby Johnstown for the children’s education” (305) and that their son Peter was educated beyond this school, continuing on in Albany, Schenectady, Montreal and Philadelphia. A letter to his parents from Philadelphia survives, in which Peter asks for a book in Mohawk “for I am Afraid I’ll lose my Indian Tongue if I dont practice it more than I do” (305). After Johnson’s death, Molly sent her daughters to the school in Schenectady, and later after the Mohawks entered the war, her older daughters schooled in Montreal (Feister 310), while two of her younger daughters were in school at Niagara (Feister 311). Though the separation from her children during wartime must have been emotionally difficult for her, their relative safety in school allowed their education to continue. History has not recorded much more about Molly Brant’s education, or to what extent her daughters were literate in Kanien’keha.

Sources and Additional Reading

Beauchamp. William M. 1881 The Indian Prayer Book. The Church Eclectic 9(5):415- 422. Utica, N.Y.

Feister, Lois M.; Pulis, Bonnie (1996). “Molly Brant: Her Domestic and Political Roles in Eighteenth-Century New York”. In Grumet, Robert S. Northeastern Indian Lives, 1632–1816. Amherst, Massachusetts: University of Massachusetts Press.

Akwesane Cultural Center website

Onondaga Nation website

Ganondagan website

Six Nations Indian Museum website

Iroqouis Museum website

Born and raised in Central NY, Michael Brewster has traveled the US extensively, but is most at home in the Finger Lakes. The beauty and history of Upstate NY continue to marvel and fascinate him. He enjoys local food, beer and live music. Find him on Twitter @brewcuse