How Central New York Fueled The Flat Earth Debate

The Flat Earth debate goes back far into history, but maybe not as far back as most would believe. In this article, we’ll explore how the Flat Earth philosophy was fueled by a few men from Central New York, including the founder of Cornell University, and even involved one of the most successful attempts at launching a hoax on the American public.

by Michael Brewster

You might have learned as a child that Christopher Columbus sailed from Spain to China to prove the world was round.

You might even have sung a song about it:

“They laughed at Columbus,

berated Columbus for saying the world was round,

so then he set sail through strong winds and gale,

to prove what he said was sound.”

Just like with stories about Pocahontas or the Pilgrims, a kernel of truth is buried deep inside the “Columbus Proves the World Is Round” story. But what people mostly remember is that as late as 1492 people thought the world was flat. This is a myth, a complete fabrication, and not based on any kind of truth at all.

People did not believe in 1492 or even 492 that the earth was flat.

So, why did people believe this Flat Earth story and why do people still believe that the “ancients” were ignorant of the earth’s sphericity? Indeed, not only do people today believe that before Columbus sailed that everyone thought the Earth was flat, we have people today who deny the Earth is spherical!

How Did People Start Thinking The Earth Was Flat?

This article will examine how people started to believe the Columbus story. It begins with three New Yorkers: the writer Washington Irving and the professors John William Draper and Andrew Dickson White.

Washington Irving made up the Columbus story in his 1828 fictionalized biography A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus. Using an invented account of the Council of Salamanca, Irving made Columbus into a hero of truth against the ignorant beliefs of the churchmen. Indeed, Columbus did face criticism over his proposed voyage, but it was based on the idea that Columbus severely underestimated the size of the globe. Using the wrong math, Columbus guessed he could sail west from Spain and reach China after 5000 kilometers.

The true distance is about four times as great, and most of the learned men in 1492 understood this. What they didn’t know was that the continents of North and South America stood in the way.

Because Irving was such a popular writer, his fictionalized account replaced the true, but largely forgotten, history. Irving pitched Columbus as a patriotic hero, and his book was read as justification for the founding of the United States of America as the home of truth.

Science Clashes With Religion

Was Irving’s fiction enough for most Americans to believe in the myth of the flat earth? Perhaps. But as the 19th Century progressed, investigations into natural philosophy continued and this created the thing we today call “Science.”

Again, popular misconceptions of persecution of “scientists” from previous centuries caused what seemed to be a logical rift between science and religion. Men like Galileo and Copernicus had been labeled as heretics and many people today believe they were burned at the stake, even though they were not. The philosopher Giordano Bruno was burned at the stake for his beliefs, and as these stories passed into popular consciousness during the 19th Century, they created a foundation for the conflict between religion— the medieval Roman Catholic Church especially— and science. By the time Charles Darwin published his writings on evolution, the English and American Protestant majority accepted that God-fearing men could investigate nature using scientific methods, because they believed they were looking into the Creator’s intentions.

John William Draper was a professor of chemistry, a photographer, and was instrumental in founding the New York University School of Medicine. His 1874 book History of the Conflict between Religion and Science furthered the conflict thesis, which is named after his title. Along with Andrew Dickson White, as we will see, his ideas were instrumental in popularizing the idea that Religion is the enemy of Science.

Central New York Joins The Religion vs. Science Debate

This story starts in the most improbable way possible, at a tidy brick house about a mile from where I live. Like many Upstate New York villages, Homer has a rich local history that has spilled over to national and international prominence at various times over the two centuries since its founding. Unlike most of these famous events and people, this particular story’s connection to Homer is nearly unknown.

Certainly, if it were more well-known, it might be seen as scandalous!

Speaking of local scandal, in the past several months the Village of Homer has embarked on the somewhat controversial task of updating its village signs. The current ones are becoming weather-worn, and as replacement plans materialized, some in the Village thought that the design of the sign could also use a bit of burnishing.

Immediately, a redesign that eliminated mention of “David Harum” sparked a firestorm that swept through the populace several times before ultimately dying down.

That Homer’s “Welcome” signs proclaim it to be a friendly town, “home of David Harum,” certainly illustrates the famous dictum of Alfred North Whitehead, a philosopher of science. Whitehead held that, “In the real world it is more important that a proposition be interesting than that it be true. The importance of truth is that it adds to interest.”

What is true here is that David Harum is a fictional character, the creation of retired Syracuse banker Edwin Noyes Westcott. Westcott’s novel fictionalized the life of horse trader David Hannum who resided in the Village of Homer during his grand heyday. The real-life Hannum became financially involved in the Cardiff Giant and made a lot of money, but died penniless in 1892. With the publishing of Westcott’s David Harum in 1898, the thinly-veiled character brought much fame to real-life town of Homer, fictionalized in the book as Homeville.

The book was a bestseller and was adapted for the stage, radio, and into a movie starring Will Rogers.

Over a century later, Homer still recognizes that interesting connection and though the local government has decided to remove the Harum name from the Welcome signs, there is no removing the Hannum-Harum association from popular culture.

Andrew Dickson White Is Born In Homer, New York

I point out this need for Homer to present itself, to project its own image into the world, because for the past two centuries, the Village of Homer has thought of itself as a reliable and trustworthy beacon of civilization. Indeed, the physical layout of the village reflects the twin lights of Religion and Education. Homer native Andrew Dickson White, who co-founded Cornell University with Ezra Cornell, recalled the village he was born into:

Homer, at my birth in 1832, about forty years after the first settlers came, was, in its way, one of the prettiest villages imaginable. In the heart of it was the “Green,” and along the middle of this a line of church edifices, and the academy. In front of the green, parallel to the river, ran, north and south, the broad main street… without exception, neat, trim, and tidy.

The current elementary school sits on the site of the former Cortland (later renamed “Homer”) Academy. Chartered in 1819, Cortland Academy was a proficient educational institution of its day. Over the years it educated many of Central New York’s leading citizens, and as a child, the building captivated White. Born November 7, 1832 to Horace and Clara Dickson White, little Andrew grew up in Homer a block from the village green.

“As a boy of five or six years of age,” White continues in his autobiography, “I was very proud to read on the cornerstone of the Academy building my grandfather’s name among those of the original founders.” When Andrew was seven, the White family moved 30 miles north to Syracuse, where Horace became a prominent banker. Though Andrew would go on to attend the renowned Syracuse Academy, the Cortland Academy “acted powerfully on my education in two ways— it gave my mother the best of her education, and it gave to me a respect for scholarship.”

As one would expect for a man who would later co-found a university, the love and respect for education would outpace all other activities in his life. “Thus began my education into that great truth, so imperfectly understood, as yet, in our country, that stores, shops, hotels, facilities for travel and traffic are not the highest things in civilization.”

I find it interesting that in this discussion of early influences, White fails to mention religion.

Certainly, the young boy walking the Homer village green must have seen the five churches surrounding the one school and perceived the importance of religion in the villagers’ lives. Indeed, he mentions his great-grandfather as a man who walked four miles to church at the age of 82, and calls his extended family and their New England neighbors “honest, straightforward, God-fearing men and women.” In remembering his mother’s father, he praises the early Homer settlers for their moral uprightness “The first public care of the early settlers.” he writes, “had been a church, and the second a school.”

So the question becomes more one of how the adult White came to view organized religion in such a poor light.

Andrew Dickson White And Religion

By White’s own account, his father was involved in the St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Syracuse, especially in its parish school. Later, he entrusted Andrew’s college preparation to a young Episcopalian scholar who went on to become a bishop. It was Andrew’s desire to enter one of the larger New England universities, but his tutor had graduated from the small Episcopalian Geneva College and in conjunction with the bishop, he swayed Horace White to place his son there.

Geneva College grew to become today’s Hobart and William Smith Colleges, certainly a fine institution, but back then was a lot more parochial than what young Andrew desired for himself. White describes his classmates as lazy sons of wealthy churchmen and he abandoned Geneva College at the end of his freshman year, against the wishes of his father. After some months of estrangement, Andrew finally entered Yale University and embarked on the course that would make him a Professor of History at the University of Michigan and lead him on to Cornell.

This story hinges heavily upon how and why Andrew Dickson White became one of the two men most responsible for creating and perpetuating an idea that from Ancient Times through the Age of Discovery at the end of the Medieval Period, people believed that the earth was flat. The popular part of this myth, that Columbus sailed from Spain believing the world to be a disk was, as we have seen, was the invention of Washington Irving. John William Draper and Andrew Dickson White both expanded on this idea to reflect what they saw as a centuries-long battle between Religion and Science.

The Draper book was published in 1874, two decades before Andrew Dickson White published History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom in 1896. However, White first advanced his ideas in a December 17, 1869 lecture. This date resonates with me as the year of the discovery of the Cardiff Giant.

Is there a connection between the hoax of the Cardiff Giant and White’s own creation of a mythical belief in false science under the guise of religion?

The Original CNY Hoax: The Cardiff Giant

For me, there’s no question that the Cardiff Giant hoax had an enormous impact on the development of Andrew Dickson White’s conception of Science as a professional venture.

First off, he devotes an entire chapter of his autobiography to the events of 1869, and though he was personally involved with the discussions of the day, his memoir is not self-aggrandizing. Instead, he examines his own scientific reaction and recounts the various declarations of other men on the subject.

A brief overview of the Cardiff Giant Hoax is in order here.

In 1869, George Hull, a businessman from Binghamton, NY, procured a gigantic piece of gypsum out in Iowa. He then had it carved in the likeness of a man, and arranged for it to be transported and buried on the farm of Stub Newell in Cardiff, NY, a small hamlet not too far south of Syracuse in the hills. The “discovery” of the Giant on the Newell farm that October created an immediate worldwide sensation. Soon after its discovery, Hull directed Newell to sell interests in the Giant, and did so to a group of men including David Hannum.

The whole story of the Cardiff Giant is an incredibly interesting topic, and far too large to cover in depth here. What is important is the reason Hull perpetrated his hoax. The most cynical can speak of the mountains of money made (and lost) subsequent to the discovery, but Hull himself maintained he did it to expose religion’s folly.

Specifically, he mentioned one Henry B. Turk, a Methodist preacher. Hull and Turk debated deep into the night on one occasion, spurred by Hull’s ridicule of Genesis 6:4, which starts off, “There were giants in the earth in those days…” Hull then hatched his plan to prey upon the literal interpretation of the Bible and prove how gullible the religious could be. The idea that the giant was thought by many to have been an ancient artifact instead of a petrified man was a bonus.

Though he was from the area, Andrew Dickson White was not in Central New York on October 16, 1869, when the Cardiff Giant was unearthed. White describes his return to Syracuse:

I had been absent in a distant State for some weeks, and, on my return to Syracuse, meeting one of the most substantial citizens, a highly respected deacon in the Presbyterian Church, formerly a county judge, I asked him, in a jocose way, about the new object of interest, fully expecting that he would join me in a laugh over the whole matter; but, to my surprise, he became at once very solemn. He said, “I assure you that this is no laughing matter; it is a very serious thing, indeed; there is no question that an amazing discovery has been made, and I advise you to go down and see what you think of it.”

Though subtle, White’s jab at religion is apparent. That a respected judge would take the Giant seriously did indeed surprise White. The next day, he and his brother took a buggy south to Cardiff. After viewing the stone figure, someone asked the co-founder of Cornell University what he thought.

Being asked my opinion, my answer was that the whole matter was undoubtedly a hoax; that there was no reason why the farmer should dig a well in the spot where the figure was found; that it was convenient neither to the house nor to the barn; that there was already a good spring and a stream of water running conveniently to both; that, as to the figure itself, it certainly could not have been carved by any prehistoric race, since no part of it showed the characteristics of any such early work; that, rude as it was, it betrayed the qualities of a modern performance of a low order.

Cornell University was founded in 1865 and grew into a major nonsectarian university in America. One would expect A.D. White, as an academic, to ignore any religious explanation for the giant’s origin and focus on the evidence at hand. Indeed, even as a sculpture, White was severely unimpressed:

Nor could it be a fossilized human being; in this all scientific observers of any note agreed. There was ample evidence, to one who had seen much sculpture, that it was carved, and that the man who carved it, though by no means possessed of genius or talent, had seen casts, engravings, or photographs of noted sculptures.

Despite his final determination, White writes, “the work was very generally accepted as a petrified human being of colossal size, and became known as ‘the Cardiff Giant.’”

White’s faith in the ability of the common man to employ reason over superstition was shaken. “At no period of my life have I ever been more discouraged.” He writes, “as regards the possibility of making right reason prevail among men.” The fact that these words were published more than three decades after the events is important, but this is a blanket sort of statement we might expect from a high-minded academic, hardly surprising in its judgment. However, White is not finished and continues, “As a refrain to every argument there seemed to go jeering and sneering through my brain Schiller’s famous line: Against stupidity the gods themselves fight in vain.” Clearly, the chance to excoriate those who would disdain science and the evidence of reason was too great for White to pass up.

Against stupidity the gods themselves fight in vain.

Friedrich Schiller, Die Jungfrau von Orleans (The Maid of Orleans) (1801), Act III, sc. vi

Certainly, the public spectacle of the Cardiff Giant, with the involvement of David Hannum and eventually P.T. Barnum, played a large part in the public’s acceptance of the hoax, despite the pronouncements of noted men of science like Dr. James Hall, New York State geologist, and Andrew White himself.

Indeed, in late November and early December, another scheme was being hatched by Barnum. Rebuffed in an offer he placed on the Cardiff Giant, Barnum contracted with a Syracuse sculptor named Carl Otto to fashion a replica. Using recent photographs, Otto made the Petrified Giant and in quick fashion Barnum had it shipped to New York City for display. Of course, the Syracuse consortium who owned the Cardiff Giant sought an injunction, but with great ceremony, Barnum had his replica paraded through massive throngs in the Manhattan streets on December 13, 1869, just days ahead of Andrew Dickson White’s breakthrough lecture on the religion vs. science conflict debate.

Might a hoax on top of a hoax have sparked White’s imagination?

The Battle-Fields of Science

On the evening of December 17, 1869 at Cooper Institute, Andrew Dickson White, President of Cornell University, gave a largely-forgotten lecture that I would argue was the genesis of one of the greatest modern conspiracy theories. He lays out his thesis explicitly:

In all modern history, interference with Science in the supposed interest of religion— no matter how conscientious such interference may have been— has resulted in the direst of evils to both Religion and Science, and invariably. And on the other hand all untrammeled scientific investigation, no matter how dangerous to religion some if its stages may have seemed, temporarily, to be, has invariably resulted in the highest good of Religion and Science.

As a history professor desiring to further science as a professional field of study, White begins his argument with a historical anecdote on what he calls “cosmography”— the doctrine of the earth’s shape, surface, and relations. White immediately starts his argument with a myth, that in Antiquity, certain men had somehow discerned that the Earth was round, and that though they were “vague” and “mixed with absurdities,” they did plant the seed. After the Dark Ages, White continues, certain brave men picked up this idea. However, “the greatest and most earnest men of the earth took fright at once.”

Before we allow him to flesh out his thesis, it is important to state without reservation that Professor White is already wrong here. According to Stephen Jay Gould, “there never was a period of ‘flat Earth darkness’ among scholars, regardless of how the public at large may have conceptualized our planet both then and now.” If we actually go back to the pre-Washington Irving histories, we can see that Gould is right, that nobody seriously disputed the earth’s rotundity. Even in the case of Columbus, it was the size of the globe in question, not its shape.

White continues by mentioning Eusebius and Lactantius as early church fathers who attacked science. He quotes Eusebius as writing “It is not through ignorance of the things admired by them, but through contempt of their useless labor, that we think little of these matters, turning our souls to better things.” Now, Eusebius did write that, but he was actually referring to what we would call today the Scientific Method— hypothesize, test, refine. The idea of speculation, that various learned men of his time could speculate the seat of the soul in the body and differ with each other, for example, was the useless labor. White says Lactantius asserted that scientific ideas were “empty and false.” White concludes that, “Even such men as Lactantius and Eusebius cannot pooh-pooh down a great new scientific idea.”

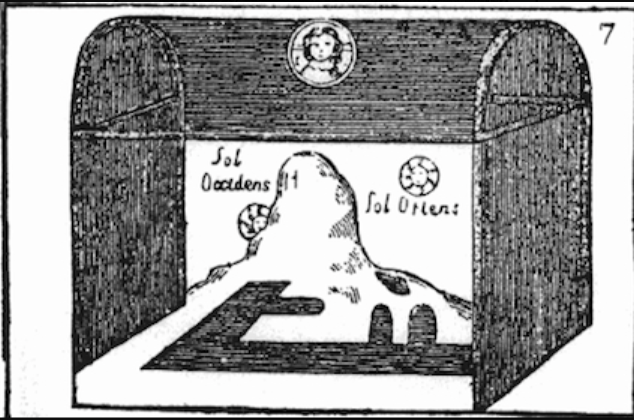

White’s lecture covers basic areas of conflict with some illustrative examples, but for him, the most enduring damage in the battle over the flat earth was wrought by the 6th Century thinker Cosmas, who wrote the book Christian Topography after traveling around the Middle East, Africa, and India. Cosmas published invaluable maps of the world in that book, but his model of the earth as flat and the heavens as a box with a curved lid is where White focuses his gaze.

Such was the great fortress built against human science in the sixth century by Cosmas, and it has stood. The innovators have attacked it in vain. The greatest minds in the Church devoted themselves to buttressing it with new texts, and to throwing out new outworks of theologic reasoning.

White moves from Cosmas to Columbus, whom he characterizes incorrectly as having been overwhelmed at Salamanca, but was a great warrior for science. Magellan, with his circumnavigation, had proven the earth was round and proved people could live on the other side of the globe, even in the Southern “Upside-down” Hemisphere.

For White, this one battle was won by Science, but at great cost. Twelve centuries of ignorance and strife forced many great thinkers into “that most unfortunate conviction that science and religion are enemies.” On the other hand, science gave religion “a far more ennobling conception of the world.”

History Of The Warfare Of Science With Theology In Christiandom

Establishing Cornell University as a nonsectarian college exposed Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White to sustained attacks for turning their backs on religion. A Master’s Thesis by Fredrika Louise Loew places these battles into the context of Cornell’s own foundational myth as a “Nonsectarian” university squarely built on Protestant principles. Indeed, it is easy to read White’s 1896 masterwork History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christiandom as being an expression of White’s own battles against religion.

However, our focus here is more about the local Central New York connections to White’s inspirations.

While White’s 1869 lecture does not explicitly touch upon the sensation of the Cardiff Giant, those fundamental ideas raised by his original analysis of the Stone Giant are infused throughout the 1896 book. In his diary for November 3, 1869, after his second visit to Cardiff, we read in his diary White’s note that “It is a very curious matter and I still think it comparatively recent.”

The fact that men of faith were ready to imbue this Giant with religious significance, while men of science could set aside prejudices and focus on actual empirical evidence, drove White into rhetorical overdrive. Throughout History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christiandom are anecdotal illustrations of how various men misinterpreted and misrepresented fossils throughout history. In most cases, White chooses to focus on how someone would find a giant fossilized bone and use it as evidence for Biblical giants. Indeed, he cites more than a dozen instances of religious men passing off reptile and mammal fossils as remains from ancient giants. The Genesis 4:6 verse was often cited, with these “Giants” having met their demise in Noah’s Deluge.

Closing Chapter XVII Part 1 of his book, White zeroes in on “mythical explanations of remarkable appearances in nature,” delving deeply into several mythologies from around the globe. Many involve giants throwing boulders at people or early churches, yet another variation on “there were giants” idea. As one might expect, a particular stone giant features prominently here, and the specifics of the anecdote White shares fit perfectly with his overall thesis.

A Flat Earth And A Swindler Of Genius

We’ve looked at how the Cardiff Giant was created, buried, and “discovered” in order to poke fun at Religion, but alternate theories were floated, one tying the Cardiff Giant to legends of stone giants found in the mythos of the Onondagas, whose traditional lands the Giant was buried. This could make a kind of sense, and White ties this into the greater stories of gods and rocks that abound. He also mentions the “theologian explained it by declaring it a Phoenician idol, and published the Phoenician inscription which he thought he had found upon it.”

In choosing this particular explanation of the Giant’s origin, White neatly ties up his “foolish” men of god argument.

Speaking of the Cardiff Giant “hoax,” White notes it is the product of “a swindler of genius.” Surely, he admires George Hull’s ingenuity, and perhaps he learned a bit from the entire spectacle. When he spends volumes railing against religion’s interference in the realms of science, Andrew Dickson White is drawing upon his own personal experiences, from his youth in Homer to his schooling in Geneva, to his witnessing the foolishness of religious men in regard to the Cardiff Giant.

As as scientific man, the steadfastness of his arguments must have been paramount to him, but as a man who had witnessed the value of bluster and showmanship in convincing the masses, White ultimately gave into that impulse when he chose to disregard the fact that no ancients of note believed in a Flat Earth.

It’s crazy to think that one of today’s greatest memes has been fueled over the last century-and-a-half by the last great hoax of America, the Cardiff Giant, and by several men with deep ties to New York State. Even more crazy is that the two hoaxes can be legitimately tied to two houses almost across the road from each other on Main Street of Homer, New York, in the heart of Upstate.

Born and raised in Central New York, Michael has traveled extensively, but is most at home in the Finger Lakes. The beauty and history of Upstate New York continue to marvel and fascinate him. He enjoys local food, beer, and live music. Find him on Twitter @brewcuse